Asthma

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory lung disorder of the airways that results in recurrent episodes of airflow obstruction, but is usually reversible. Inflammation causes varying degrees of obstruction in the airways, which leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, sensation of chest tightness, and cough, particularly at night and in the early morning.

Although the exact mechanisms that cause asthma remain unknown, multiple triggers are involved.

- Allergic asthma may be related to allergens, such as dust, pollen, grasses, mites, roaches, moulds, animal dander, or latex.

- Asthma that is induced or exacerbated during physical exertion is called exercise-induced asthma (EIA) or exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB). Typically, this type of asthma occurs after vigorous exercise, not during it.

- Respiratory infections (particularly viral) are the major precipitating factor of an acute asthma attack.

- Some patients with asthma have chronic sinus and nasal problems. Nasal problems include allergic rhinitis, either seasonal or perennial, and nasal polyps.

- Sensitivity to specific drugs (e.g., Aspirin and other NSAIDS) may occur in some asthmatic persons, especially those with nasal polyps and sinusitis, resulting in an asthma episode.

- Tartrazine (yellow dye no. 5, found in many foods) and sulphites (e.g., sodium metabisulphite), widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries as preservatives and sanitizing agents can precipitate asthma symptoms. Sulphites are commonly found in fruits, beer, and wine and are used extensively in salad bars to protect vegetables from oxidation.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can also trigger asthma.

- Various air pollutants, cigarette or wood smoke, vehicle exhaust, diesel particulate, elevated ozone levels, sulphur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide can trigger asthma attacks.

- Physiological stress that elicits emotional responses such as crying, laughing, anger, and fear can lead to hyperventilation and hypocapnia, which can cause airway narrowing.

- Occupational asthma occurs after exposure to agents of the workplace. These agents are diverse and include wood dusts, laundry detergents, metal salts, chemicals, paints, solvents, and plastics.

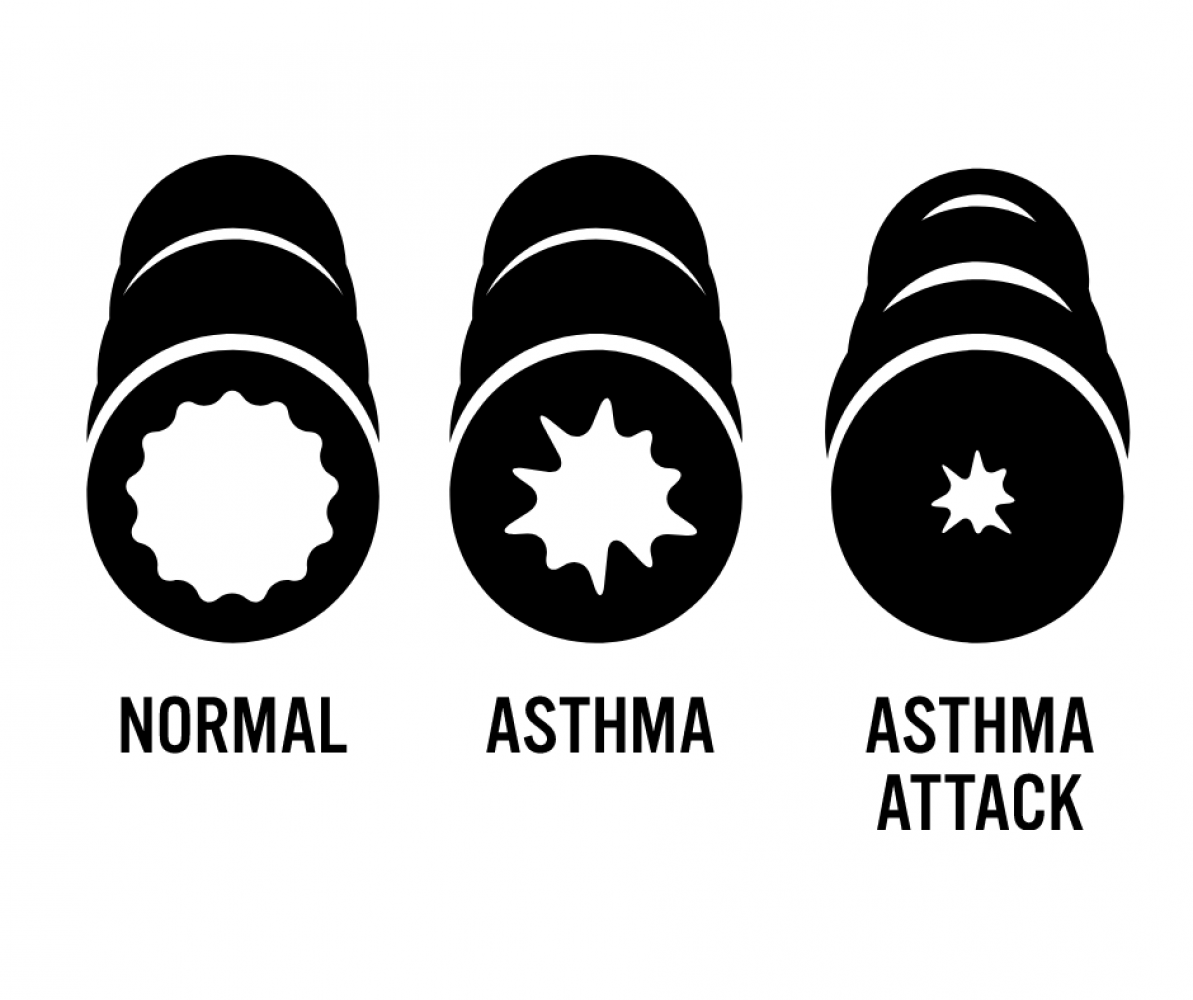

- The hallmarks of asthma are airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness.

- The degree of bronchoconstriction is related to the degrees of airway inflammation, airway hyper-responsiveness, and exposure to endogenous and exogenous triggers (e.g., infections, allergens, histamine, and other cell mediators).

- Exposure to allergens or irritants initiates an inflammatory cascade involving multiple cell types, mediators, and chemokines. Typically, there are two possible types of asthmatic responses to stimuli: an early-phase response and a late-phase response.

- The characteristic clinical manifestations of asthma are wheezing, cough, dyspnea, and chest tightness after exposure to a precipitating factor or trigger. Expiration may be prolonged.

- In some patients with asthma, cough is the only symptom, which is termed cough variant asthma.

- The severity of asthma is determined from the frequency and duration of symptoms, the presence of persistent airflow limitation, and the medication required to maintain control.

- Severe acute asthma can result in complications such as pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, acute cor pulmonale with right ventricular failure, and severe respiratory muscle fatigue that leads to respiratory arrest (which can be fatal).

- Two main features must be considered in the diagnosis of asthma: symptoms and variable airflow obstruction. A detailed history is important in determining whether a person has had previous attacks of a similar nature, often precipitated by a known cause or trigger.

- In all patients who are able to perform pulmonary testing, clinically suspected asthma should be confirmed with objective lung measurements that demonstrate post-bronchodilator reversible obstruction, variable airflow limitation over time, or airway hyper-responsiveness. Spirometry is the preferred test for diagnosing asthma; alternative lung testing includes variations in PEFR and bronchoprovocative challenge testing.

- Patient education remains the cornerstone of asthma management and should be carried out by health care providers providing asthma care. Several components enable successful management of asthma: (1) establishment of a confirmed diagnosis through the use of objective measures; (2) development of a partnership between health care providers and the patients and families affected by asthma; (3) limited exposure to triggers; (4) education of patients; (5) appropriate pharmacotherapy; (6) continuous assessment and monitoring of asthma control and severity; (7) implementation of a written action plan; and (8) ensuring regular follow-up.

Medications

Medications are divided into two general classifications: (1) relievers (“rescue” medications used intermittently as required to ease asthma symptoms) and (2) controllers (maintenance therapy used on a daily basis, typically twice a day).

- Because chronic inflammation is a primary component of asthma, corticosteroids, which suppress the inflammatory response, are the most potent and effective anti-inflammatory medication currently available to treat asthma.

- Mast cell stabilizers are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that inhibit the IgE-mediated release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells and suppress other inflammatory cells (e.g., eosinophils).

- The use of leukotriene modifiers can successfully be used as add-on therapy to reduce (not substitute for) the doses of inhaled corticosteroids.

- Short-acting inhaled β2-adrenergic agonists are the most effective drugs for relieving acute bronchospasm. They are also used for acute exacerbations of asthma.

- Methylxanthine (theophylline) preparations are less effective long-term control bronchodilators than β2-adrenergic agonists.

- Anticholinergic agents (e.g., ipratropium [Atrovent], tiotropium [Spiriva]) block the bronchoconstricting influence of the parasympathetic nervous system.

- One of the major factors for determining success in asthma management is the correct administration of drugs.

- Inhalation devices include metered-dose inhalers (with or without spacers), dry powder inhalers, and wet nebulizers.

- A goal in asthma care is to maximize the ability of the patient to safely manage acute asthma episodes via an asthma action plan developed in conjunction with the health care provider. An important nursing goal during an acute attack is to decrease the patient’s sense of panic.

- Written asthma action plans should be developed together with the patient and family, especially for those with moderate or severe persistent asthma or a history of severe exacerbations.

Clinical Manifestations

The signs and symptoms of asthma can be easily identified, so once the following symptoms are observed, a visit to the physician is necessary.

- Most common symptoms of asthma are cough (with or without mucus production), dyspnea, and wheezing (first on expiration, then possibly during inspiration as well).

- Cough. There are instances that cough is the only symptom.

- Dyspnea. General tightness may occur which leads to dyspnea.

- Wheezing. There may be wheezing, first on expiration, and then possibly during inspiration as well.

- Asthma attacks frequently occur at night or in the early morning.

- An asthma exacerbation is frequently preceded by increasing symptoms over days, but it may begin abruptly.

- Expiration requires effort and becomes prolonged.

- As exacerbation progresses, central cyanosis secondary to severe hypoxia may occur.

- Additional symptoms, such as diaphoresis, tachycardia, and a widened pulse pressure, may occur.

- Exercise-induced asthma: maximal symptoms during exercise, absence of nocturnal symptoms, and sometimes only a description of a “choking” sensation during exercise.

- A severe, continuous reaction, status asthmaticus, may occur. It is life-threatening.

- Eczema, rashes, and temporary edema are allergic reactions that may be noted with asthma.

Triggers & Prevention

Some, but not all the possible things that could trigger an asthma attack, knowing them means you might be able to avoid them thereby preventing a possible attack:

- Allergens. Allergens, either seasonal or perennial, can be prevented through avoiding contact with them whenever possible.

- Knowledge. Knowledge is the key to quality asthma care.

- Evaluation. Evaluation of impairment and risk are key in the control.

Possible Complications

- Status asthmaticus. Airway obstruction in status asthmaticus often results in hypoxemia.

- Respiratory failure. Asthma, if left untreated, progresses to respiratory failure.

- Pneumonia. Mucus that pools in the lungs and becomes infected can lead to the development of pneumonia.

ADPIE

Assessment

- Positive family history. Asthma is a hereditary disease, and can be possibly acquired by any member of the family who has asthma within their clan.

- Environmental factors. Seasonal changes, high pollen counts, mold, pet dander, climate changes, and air pollution are primarily associated with asthma.

- Comorbid conditions. Comorbid conditions that may accompany asthma may include gastroeasophageal reflux, drug-induced asthma, and allergic broncopulmonary aspergillosis.

Nursing Assessment includes:

Assessment of a patient with asthma includes the following:

- Assess the patient’s respiratory status by monitoring the severity of the symptoms.

- Assess for breath sounds.

- Assess the patient’s peak flow.

- Assess the level of oxygen saturation through the pulse oximeter.

- Monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Nursing Diagnosis

Possible nursing diagnosis appropriate for a patient with asthma include:

- Ineffective airway clearance related to increased production of mucus and bronchospasm.

- Impaired gas exchange related to altered delivery of inspired O2.

- Anxiety related to perceived threat of death.

Planning

Possible Planning or Goals:

- Maintenance of airway patency.

- Expectoration of secretions.

- Demonstration of absence/reduction of congestion with breath sounds clear, respirations noiseless, improved oxygen exchange.

- Verbalization of understanding of causes and therapeutic management regimen.

- Demonstration of behaviors to improve or maintain clear airway.

- Identification of potential complications and how to initiate appropriate preventive or corrective actions.

Interventions

- Assess history. Obtain a history of allergic reactions to medications before administering medications.

- Assess respiratory status. Assess the patient’s respiratory status by monitoring the severity of symptoms, breath sounds, peak flow, pulse oximetry, and vital signs.

- Assess medications. Identify medications that the patient is currently taking. Administer medications as prescribed and monitor the patient’s responses to those medications; medications may include an antibiotic if the patient has an underlying respiratory infection.

- Pharmacologic therapy. Administer medications as prescribed and monitor patient’s responses to medications.

- Fluid therapy. Administer fluids if the patient is dehydrated.

Evaluation

- Maintenance of airway patency.

- Expectoration or clearance of secretions.

- Absence /reduction of congestion with breath sound clear, noiseless respirations, and improved oxygen exchange.

- Verbalized understanding of causes and therapeutic management regimen.

- Demonstrated behaviors to improve or maintain clear airway.

- Identified potential complications and how to initiate appropriate preventive or corrective actions.

Katherine - your asthmatic patient

Katherine is a 24-year-old female college student. She identifies as female - using pronouns she/her. She is in transition male to female, has had top surgery aprox 6 months ago.

She is admitted to the emergency department (ED) with a severe asthma attack after playing a college soccer match.

She is accompanied by her team mate Sharon, who drove her to the ED.

On an initial assessment you see that she is sitting in an upright position, using her accessory muscles to breathe. She appears restless and anxious. Her vital signs are T 36.9° C, HR 128 beats/min, R 34/min, BP 160/82. Auscultation indicates faint wheezing on inspiration and expiration, and her expirations are prolonged. Hyperresonance is noted upon percussion. Katherine manages to tell you that she has a long history of asthma, diagnosed when she Wass 3. She tells you that this is the worst attack she has ever experienced. She cannot identify any triggers that she may be sensitive to and has never been tested for allergens. She does not smoke or use alcohol due to the effect it has on her transitioning meds. She had been using a bronchodilator metered-dose inhaler about once a day but has misplaced it. She also has a peak flow meter but has never used it.